By Brett Milam

Editor

Suicide in the United States, Ohio and in Clermont County remains an ongoing and preventable public health crisis, with national, state and county coalitions working to curb an increasing rate of suicides over the last decade, and that has remained salient as those same coalitions deal with the increased strain from COVID-19.

Nationally, in 2017, 47,173 people died by suicide, an average of 129 suicides a day, which is nearly two and a half times more than homicides (19,510), making it the 10th leading cause of death. That’s up from 2007’s figure of 34,598, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

At the state level, in 2009, there were 1,341 suicides, which increased to 1,804 suicides by 2018.

Clermont County has seen a different, more positive trend: in 2013 and 2014, there were 31 and 34 suicide deaths, respectively. By 2017, that number was 25.

Karen Scherra, executive director of the Clermont County Mental Health and Recovery Board, told The Sun in April that she was concerned with an increase in mental health issues, or other problems developing, such as anxiety.

In an August follow-up, Scherra said, “Everything you read about mental health issues and the pandemic points to expected increases in need for mental health services.”

The CDC has reported that 40 percent of adults in the United States are struggling with anxiety and depression, a higher rate than the one in five indicated through research, and other areas have reported spikes in suicides and calls to hotlines, she said.

While there hasn’t been those indicators in Clermont County yet, Scherra said they will be watching the numbers to be “prepared to handle any increased service needs.”

“The longer that anxiety-provoking situations continue — people kept away from family, friends, and social interactions, the impact on families caused by the changing landscape of children going to school and participating in sports, continued unemployment and financial difficulties, the concerns about becoming infected with the coronavirus, etc. — the more likely it is that mental health-related issues will emerge,” she said.

Anxiety and depressive symptoms are being reported more, but to date, the county has not seen an increase in deaths from suicide.

New report sheds light on suicide’s impact across Ohio, including Clermont County

A new report on suicide shows its impact across Ohio and specifically within Clermont County between 2009 and 2018.

Multiple state coalitions and partners, as well as Clermont County’s own MHRB, have been working to prevent suicides in that timespan.

The Mental Health & Addiction Coalition, Ohio Alliance for Innovation in Population Health and Ohio Suicide Prevention Foundation produced, “Suicide in Ohio: Facts, Figures, and the Future,” as a report comprised of three installments to provide an “overview of state and regional-level suicide data, as well as data about the impact of and community responses to suicide in the northeast and southwest sectors of the state,” according to the report’s press release.

MHAC operates regional hubs in the Northeast and Southwest corners of the state, allowing them to work with members in 13 counties, including Clermont County, and break down the data deeper into even township and municipality level data, with the hope of providing opportunities for targeted responses.

“Too many Ohioans don’t receive the mental health and substance use disorder prevention, treatment, and support services they need. That can, and must, be changed if we are going to reduce the devastating impact of suicide across Ohio,” Joan Englund, executive director of the MHAC, said. “Armed with the detailed data included in our report, local, state and federal policymakers, and other community leaders can take the steps needed to save the lives of Ohioans.”

Every day in Ohio, about five people died by suicide, more than three times the homicide rate. In 2018, there were 564 homicides, and 1,836 suicides.

Between 2009 and 2018, 15,563 people died by suicide in Ohio, with suicides going up in that period from 1,341 suicides in 2009 compared to 1,836 in 2018. It’s the leading cause of death among Ohioans 10-14 years of age, and the second leading cause of death among those 15-34 years of age.

At 79 percent of total reported suicides, males overwhelmingly died more often by suicide than females.

The data — broken down by age over the timeframe — also indicated that the highest rate of death by suicide was in adults age 60 and over (3,684), followed by the 50-59 age group at 3,152. Deaths by suicide in children ages 14 and under nearly doubled from 15 in 2009 to 29 in 2018. Of the total deaths by suicide over the 10 years studied, 174 of those deaths were in the 14-and-under age group. The 60 and over age group had the second highest increase (80.9 percent) over the study.

Rick Hodges, director of The Alliance, said suicide is a public health issue and hopes these collaborative installments [from the report] would help to inform state- and community-level discussions surrounding how the risk of suicide can be reduced.

“This research provides a voice for the silent tragedy taking place around us,” Hodges said. “It speaks to this disease of despair and calls us to act with empathy and compassion; it shows us how we need to improve opportunities for, and access to, care.”

Recent projections by the Meadows Mental Health Policy Institute estimate a 17 percent increase in deaths by suicide in Ohio for every 10 percent increase in the unemployment rate. Ohio’s unemployment rate grew to 16.8 percent in May 2020 (an increase of 12.6 percent since December 2019), creating a potential environment in which suicide deaths could increase across the state.

Clermont County’s unemployment rate spiked to 13.9 percent in April, and has since made a modest recovery to 9.4 percent in June. But that still represents the worst unemployment numbers in nearly a decade since June 2011’s 9.7 percent.

A deeper dive into Clermont’s numbers

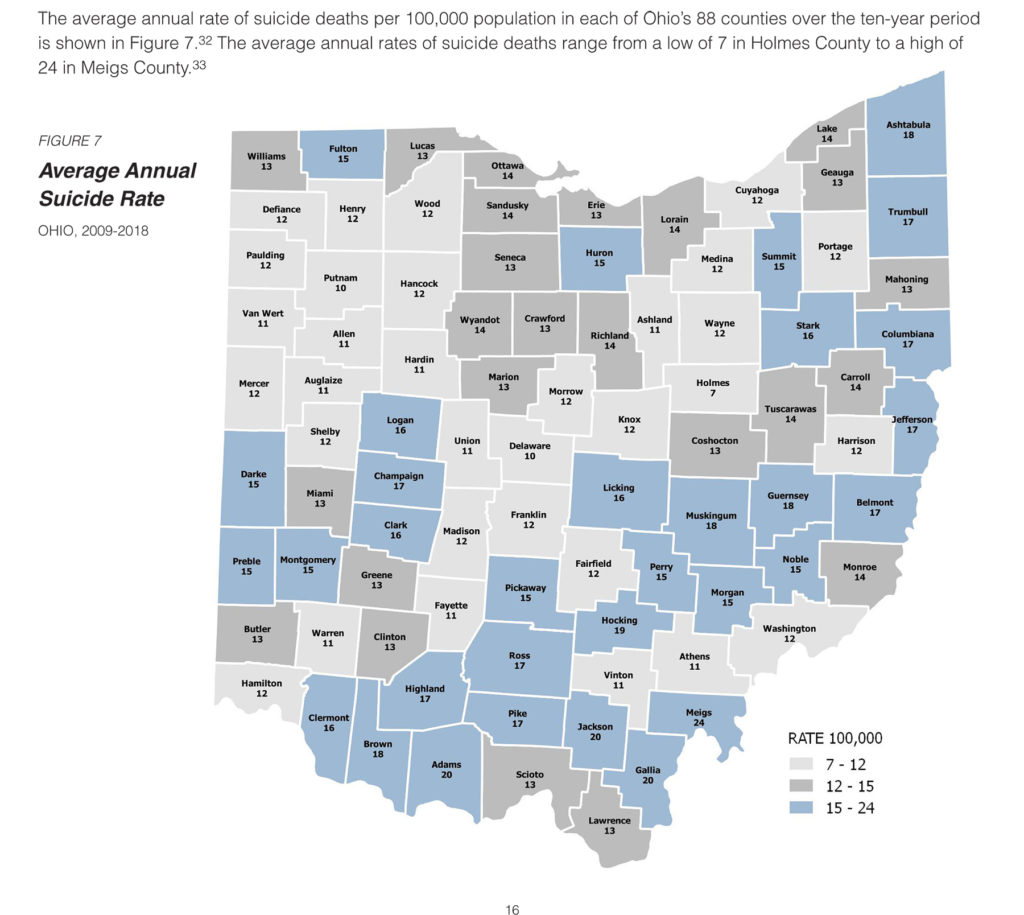

In the Southwest Ohio region (for MHAC, that includes Brown, Butler, Clermont, Clinton, Hamilton and Warren Counties), per 100,000 residents, Clermont has the second highest rate of suicide at 16, behind only Brown County at 18. Neighboring Butler and Hamilton Counties have rates of 13 and 12, respectively.

Looking at the data as broken down by township/city in the county for a more targeted approach, Scherra said that’s a possibility.

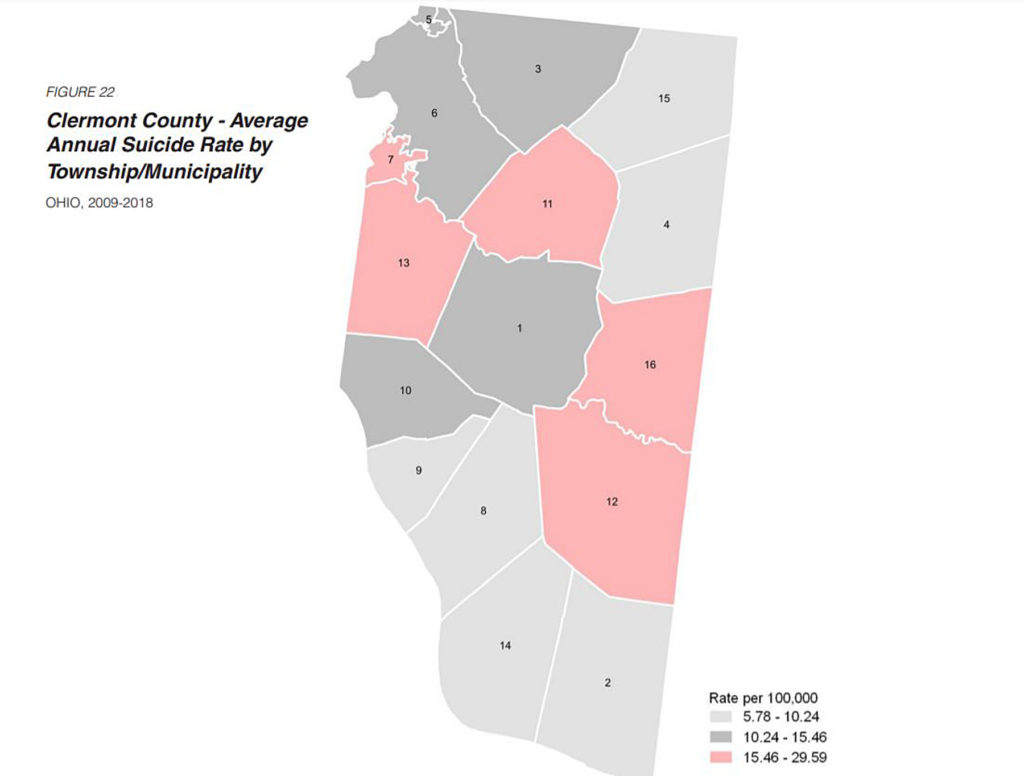

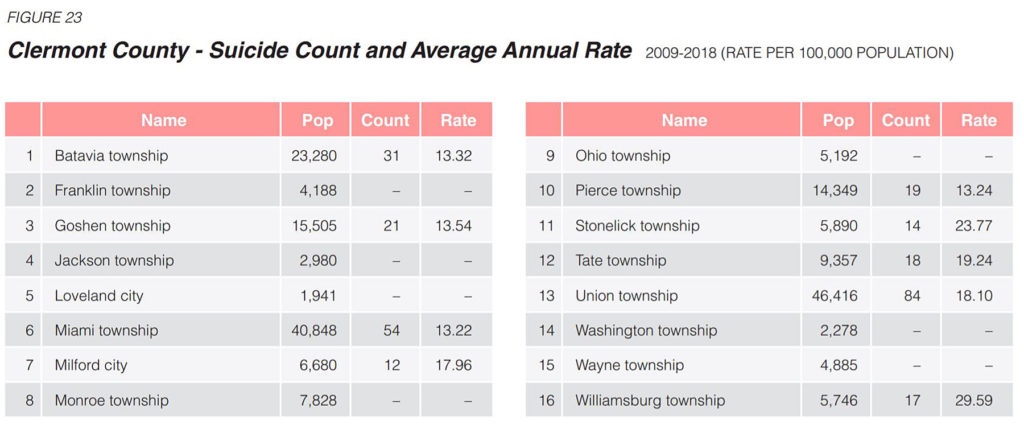

The breakdown for the average annual rate of suicide per 100,000 population:

– Williamsburg Township (population 5,746): 29.59 (17 suicide deaths).

– Stonelick Township (population 5,890): 23.77 (14 suicide deaths).

– Tate Township (population 9,357): 19.24 (18 suicide deaths).

– Union Township (population 46,416): 18.10 (84 suicide deaths).

– City of Milford (population 6,680): 17.96 (12 suicide deaths).

– Goshen Township (population 15,505): 13.54 (21 suicide deaths).

– Batavia Township (population 23,280): 13.32 (31 suicide deaths).

– Pierce Township (population 14,349): 13.24 (19 suicide deaths).

– Miami Township (population 40,848): 13.22 (54 suicide deaths).

Note: Specific data was not available for the townships of Franklin, Jackson, Monroe, Ohio, Washington, and Wayne, or the city of Loveland.

MHRB working on an updated strategic plan

As of September 2019, the Clermont County Suicide Prevention Coalition, which is managed by MHRB, has not met, but the Board is in the process of restarting the Coalition, and “establishing a new vision and mission statement, and a new strategic plan,” according to the report.

While there is not currently an explicitly stated suicide prevention/reduction plan in the MHRB’s Strategic Plan, Scherra said they are working with the Ohio Suicide Prevention Foundation, through a grant, to update the plan. They are also completing a “community readiness assessment” that will help guide the development of a “robust, data-driven strategic plan,” she said.

That assessment will be completed by the end of September.

“Once the assessment is done, the Coalition can begin developing goals and objectives related to community needs,” she said. “The Board’s Community Plan submitted annually to the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services also includes goals and objectives related to suicide prevention.”

The coalition includes representatives from a variety of populations and sectors, including media, schools, youth-serving organizations, law enforcement, healthcare professionals, and government agencies, according to the report.

Most of the efforts have gone toward awareness and education campaigns, promoting the crisis hotline.

“The coalition focuses on survivors of suicide, individuals with mental and/or substance use disorders, youth 18-24, and first responders,” the report said. “The resources available for youth are strong, while adult suicide prevention services need improvement.”

Scherra agreed with the assessment that adult suicide prevention services needs improvement in the county.

“Most of our suicide prevention efforts have been focused on youth. With still unknown effects of the pandemic on adults, it’s important to educate Clermont County residents that help is available if you are experiencing depression, anxiety, or are thinking of hurting yourself or attempting suicide,” she said. “Friends and family members can also call for assistance if they think someone they know may be struggling with mental health issues.”

The Coalition provides broad marketing of the Clermont County Crisis Hotline, Scherra said, and has targeted advertising to high risk groups, but it can be more difficult to reach the adult population compared to youth, who are often reached through the schools.

“The new strategic plan will address this population, and the high-risk population of middle-aged men,” she said.

Renewal levy on November ballot

MHRB spends about $474,650 for suicide-related crisis services, with $160,000 of that through a OhioMHAS Engage SAMHSA grant for individuals with developmental disabilities. Of the $139,000 spent in suicide prevention, about $43,000 goes to the schools. Child Focus, Inc. also receives funds to provide prevention, intervention and postvention services. The National Alliance on Mental Illness also provides a suicide prevention program.

“Providing these services, aligning with agencies to use the same screening assessment, and partnering with schools to provide school-based services are strengths that exist in the county,” the report noted.

On the November ballot this year, MHRB has a .75-mill renewal levy. The levy would generate $3.1 million per year and cost the owner of a $100,000 home $20.91. The previous levy campaign in 2015 resulted in passage of a .5-mill renewal plus a .25-mill increase, the first increase successfully passed since the levy began in 1980, according to county officials.

MHRB is at the nexus of providers of a variety of mental health and drug and alcohol services, including crisis intervention and residential treatment. Services also extend to the schools and a program at the Clermont County Jail that screens inmates while in jail and connects them to services. In addition, the Board has the Opiate Task Force, and the crisis hotline.

Scherra said passage of the levy is critical to “our ability to maintain current services and address newly identified needs.”

“We extended last fiscal year’s contract with providers for three months, to give us time to understand our full financial picture and to determine the greatest needs for services to which funds must be directed,” she said.

County expands mobile crisis to 24/7 services

One of the items noted in the report is that with more state crisis funding, MHRB said it could expand its mobile crisis to be available around the clock or perhaps to establish a crisis stabilization center with the local hospital.

Effective Aug. 30, Scherra said the mobile crisis was expanded to 24/7 services, with funding through a two-year federal grant obtained by Greater Cincinnati Behavioral Health Services, which will contract with Child Focus, the operator for mobile crisis, to provide the funding.

“We will review the number of calls to the mobile crisis during the expanded hours to determine if it is beneficial to sustain the additional hours,” she said. “We continued to monitor the times that ‘mental health calls’ are received by 9-1-1, and we have implemented the hours for mobile crisis to match the times that most calls are received.”

The expanded services also come on the heels of a state grant last year that allowed Mobile Response and Stabilization Services to children and families through a clinician and peer Parent Support Partner, a specific intervention service that supports families whose children receive services through a community mental health service provider.

A crisis stabilization center would look like a “no wrong door” triage center, which would include a crisis stabilization unit. That center would be for people experiencing behavioral health concerns and need mental health treatment, but who do not necessarily hospitalization, Scherra explained.

“No wrong door” is the concept that there is “no wrong door” for those seeking services.

“The facility should have no wrong door so that anyone who is experiencing a behavioral health concern will be admitted for assessment regardless if it is substance use or mental health related,” Scherra said.

There currently exists three options for people experiencing a behavioral health concern: jail, hospital or mobile crisis.

“These options are not always appropriate and sometimes can make the situation worse,” Scherra said. “This center would allow first responders to take individuals in a behavioral health crisis to a facility where they can be assessed to determine the appropriate level of care that is needed, whether it be hospitalization or crisis stabilization.”

That individual can then be connected to community treatment and “unnecessary hospitalization and jail can be avoided,” she added.

Coalition in a better place now than in the past

“Most of our prevention efforts have been county-wide or school-based, but targeting certain townships through mailings, billboards, holding a town hall meeting (as we did at the height of the opioid epidemic) or other activities will be considered, in collaboration with the Suicide Prevention Coalition,” Scherra said. “The Suicide Prevention Coalition has done targeted intervention in high-risk areas throughout the years and will continue to do so.”

She said the Coalition is in a better place now than in the past for several reasons.

“The Coalition membership has received various trainings on Coalition development, data collection and strategic planning, and as a result, is using data to drive prevention efforts in Clermont County,” she said. “The Coalition has better tools to assist with prevention efforts in the community, and has a broader membership of key community partners, which increases our reach to all residents.”

Awareness of prevention resources, including the Crisis Hotline, has increased over the last 10 years, she said.

In particular, Scherra cited the decrease in youth suicides in the past 10 years.

“While suicides are continuing in our county, and it is hard to measure prevention outcomes, it is believed that the fact that our suicide rate has not substantially increased in the past several years is a sign that the prevention efforts are working and more people are reaching out for help,” she said.

Resources are available

If you’re feeling suicidal, please talk to somebody.

For more information, call MHRB at 732-5400 or check ccmhrb.org or MHRB’s Facebook page for more information.

The Clermont County 24/7 Crisis Hotline is: 528-SAVE (7283).

You can reach the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255; the Trans Lifeline at 877-565-8860; or the Trevor Project at 866-488-7386. Text “START” to Crisis Text Line at 741-741. If you don’t like the phone, consider using the Lifeline Crisis Chat at www.crisischat.org.