By Brett Milam

Editor

Undeclared and undecided about sums up the situation in the village of Newtonsville after the Nov. 5 election. Unnecessary may be another word, depending on who you talk to.

After all, the three-term mayor, Kevin Pringle, “lost” by two votes to “Write-in: Undeclared,” 10 to eight. Pringle’s been the mayor since January 2012. Lost is in scare quotes because he didn’t actually lose since those 10 write-in votes do not count.

Nobody filed a valid candidate petition to be placed on the ballot for member of council, either, with two seats up, but write-in candidate Gina Maiorana received 10 votes, and “Write-in: Undeclared” received seven.

Pringle and Maiorana filed a declaration of intent to be a write-in candidate for their respective elected offices, Julia Carney, director of the Clermont County Board of Elections, explained.

“In Ohio, the candidate must file this declaration of intent to be a write-in candidates for any votes cast for them to be counted as a valid vote for the candidate,” she added. “Undeclared is a placeholder in the election report, meaning that the vote was not for a declared write-in candidate. Often times voters will write in their own name, or someone they know, or a celebrity.”

She continued, “Since these are not a valid declared write-in candidate, all of these votes are classified as undeclared, for ease of reporting results. None of the votes classified as undeclared count towards a candidate because they are not valid votes.”

In other words, Pringle is the winner for another term as mayor.

The village also teeters on the precipice of nonexistence after eight voters swayed the Nov. 5 election in favor of dissolving. With a population of 395, previously projected to increase by one in 2023, and 180 registered voters, 106 ballots were cast: 56 voted to dissolve, 48 voted not to, and two neglected to weigh in.

Plan A: The Ohio Supreme Court

While the next steps seem clear — folding into Wayne Township, and the township assuming service duties in the village — Pringle, who was against dissolve, is hoping the Ohio Supreme Court will save the village.

Otherwise, if the Supreme Court upholds the Twelfth District Court of Appeals’ ruling against Pringle, the village will be no more.

Worse to Pringle, that decision will set a precedent for voters to skirt legislative bodies, like village councils, and go straight to county board of elections to dissolve. That would be a “disaster,” he said.

As previously reported, Pringle argued in court filings that contrary to Ohio Revised Code, the village didn’t get the petitions to dissolve the village, and “therefore, could not act within the 30 days allotted … before the petition was presented to the Board of Elections.”

The Twelfth District disagreed with Pringle, saying voters have the option of choosing the process for placing the issue before their fellow electors, and “we see no valid reason why petitions to surrender must first be filed with the legislative authority.”

Judge Mike Powell dissented, saying the ORC language was phrased awkwardly, and he agreed with Pringle that the petitions must be presented to the legislative authority first, and then ignored for 30 days prior to going to the County Board of Elections.

Pringle appealed the decision up to the Ohio Supreme Court. While the initial complaint to the Twelfth District was from village coffers at the tune of $5,000, the appeal to the Supreme Court has been on Pringle’s own dime — which he acknowledges might not be a tenable situation.

That’s why the former mayor has a back-up plan: for a 501(c)(3), such as recreational group, a historical society or a library foundation to be a de facto government in the village, organizing the events villagers have come to expect. Those are events include Santa with the kids, Easter egg hunts, and so on.

“You don’t want to just take all those community events away,” Pringle said.

Pringle said he thinks that goal is very “realizable.”

The group, in whatever form it took, would also help maintain the records.

“I don’t think the township has much interest in our records, per se,” he said.

Financial caution escalates to an emergency

Pringle acknowledges that the village has been struggling financially.

In 2016, Dave Yost, then-Ohio Auditor, placed the village on fiscal caution, citing “major deficiencies in the financial records.” The village was on the “unauditable” list, and had to come up with a plan within 60 days to correct the issues.

Auditors could not determine fund balances for 2014, 2015, and 2016.

The village was using a program called Uniform Accounting Network, a software package that supports Ohio local governments’ accounting, payroll and financial management activities. It was created by the Auditor’s Office, according to its website.

However, one of the fiscal officer’s disconnected the paperwork from UAN in 2014 but did not tell Pringle or the village council. When they asked a new fiscal officer to conduct an internal audit in 2015, they discovered how much paperwork had not been filed, according to Pringle.

Pringle said he was holding mayor’s court, and for judicial ethical reasons, didn’t want to get too close to the fiscal officer and the finances.

In January 2017, at the direction of the Auditor’s Office, according to Pringle, the village instituted a one percent earnings tax.

“I didn’t really want it, back in 2016, going into 2017, and I would prefer kind of a levy approach,” Pringle said.

In the past two years, two different levies have failed when put to voters. A 2017 tax levy failed 37 to 26; and a 2018 police tax levy failed 57 to 38.

The Regional Income Tax Agency also didn’t notify many people, which added to the grievance, Pringle said.

By May 2018, an auditor’s report showed $700 in undocumented spending, and a violation of the state’s laws governing conflicts of interest.

Dan Burke, the fiscal officer at the time, and his predecessor, Rhonda McVey, were ordered to repay a combined $696 to the village for failing to maintain supporting documentation for the spending.

All of the questioned spending occurred during 2014 and 2015.

There was also the issue of an ethics violation stemming from a former council member’s vote to approve a $1,000 contract for her husband to build a Frisbee golf course. Under state law, Theresa Baker should have abstained from voting when council considered the contract in July 2015, Yost said.

Aside from that, Yost also said the village wasn’t properly maintaining minutes and other records per ORC.

In June of this year, Keith Faber, Ohio Auditor, placed the village on fiscal emergency. The request for a financial analysis came from Pringle, which showed that three of the six emergency conditions were met:

– significant past due accounts payable.

– substantial deficit balances in village funds.

– a sizable deficiency when the village’s treasury balance is compared to the positive cash balances of the village’s funds.

Accounts payable from the village’s general fund exceeded available fund receipts by $61,092, and the village had a $112,853 deficit in the general fund, with a treasury deficit of $33,616.

The plan to dissolve took Pringle by surprise

Pringle said one of the plans for attempting to right the financial woes of the village was to sell the administration building, located at 794 Wright St. The sale would be under $200,000, and that would help with the deficit.

Of course, that’s a short-term fix since the building couldn’t be re-sold year-after-year, so Pringle said they would have to do annexations of a couple streets, and bring the police force to part-time for longer-term fixes.

“I was developing a plan to really take us 10 years out on that,” he said.

Even so, there was momentum to dissolve, particularly coming from one of the newer council members Adam Roosa. He was appointed to council in the fall of 2018.

That momentum took Pringle by surprise.

“Because I didn’t take it 100 percent seriously at the beginning. I thought it was sort of just complaining,” Pringle said.

Pringle agreed with Roosa’s dislike of the earnings tax, he said, but mathematically he didn’t know if he could repeal it.

“I was somewhat alarmed, but I thought that it was so easily defeatable, that it was an easy sell, that we’d easily win it, but I didn’t stress it as much as I wanted to,” he said.

Pringle said he wanted to offer a constructive change, which to him was a commission plan reform of the village government. Instead of having a six council members and a mayor, the government would shrink down to three commissioners. It’s a provision allowed for in section 705.41 of the ORC.

That issue was also on the ballot, and voters rejected it 62 to 28.

“Maybe that, to be very truthful, I’m not sure if that helped confuse people more,” he said. “But see, the idea was, if his [Roosa’s] plan was destructive, this keeps the village, but has some changes.”

One of the other issues, as outlined earlier with the lack of official candidates for council, is that none of the council members wanted to officially re-run: they expect to be appointed by Pringle.

“I didn’t like that, I kind of resented that a little bit,” he said. “And I thought in a small village, three’s easier to elect than seven people.”

‘Confusion’ about the vote

On Nov. 25, Pringle filed with the Clermont County Common Pleas Court against the Clermont County Board of Elections and the Clermont County Recorder to temporarily enjoin and restrain the certification of the results.

Pringle also said they’ve gathered 33 signatures to file a protest in court.

“What that would be based on: did people get confused about the vote?” he said. “You have to ask those people, did they pull the wrong lever?”

Despite all that’s going on, Pringle said he looks forward to helping the village get out of the “financial morass” it’s in come 2020.

Pringle said with the township expected to take over services, he’s concerned the township wouldn’t want to use electricity and heating in the administration building. He’s also worried about police coverage, saying it’ll be a “drive-by sheriff” providing that coverage now.

Pringle said he’s also concerned that the speed limit through the village could increase from 25 mph to 35 mph.

“Some things you don’t think about happening do happen and that would be one of the byproducts,” he said.

Pringle also said he wishes the village still had a website. The village previously had one in 2014 and lost it in 2015, and he said perhaps a website or a newsletter would have helped with communication.

Without that ability to communicate, you’re losing touch, Pringle said, which he said may have been part of why the vote went the way it did.

“I think that most of the people I worked with really intended good for the village,” he said. “I didn’t see personal agendas really happening; I think they all tried to work together for the village.”

Hunt points to an outsider

Sandy Hunt, vice-mayor of the village, who has been on council for the last five years, viewed Roosa as an outsider, and someone who misled voters on the dissolve issue. She said it was “odd” that after Roosa was appointed to council, he started asking for the ordinances and back books.

“I just thought it was kind of strange your very first meeting — you’ve never been a council member before — you’d think you’d get a feel for things first instead of making demands on your first meeting,” Hunt said.

Hunt said she noticed Roosa was commenting and following along on the Facebook page of Christopher Hicks, committee member of the Union Township Republican Party, which furthered her view of Roosa as an outsider.

“And I thought, that’s really odd, he represents the village, he’s employed by the village, why would he make comments like that?” she said.

She noted that it’s a free county, and Roosa can say what he wants, but then after that, the dissolve issue came up, and it “snowballed.”

The council meetings became unpleasant and filled with animosity, Hunt added.

An issue driving the push to dissolve, among other fiscal issues, was the one percent earnings tax.

“Why just burn down the whole place because you don’t like their one percent tax?” Hunt asked.

Hunt said the council was planning on getting rid of the tax “anyways” at the beginning of next year.

She also thought Roosa confused voters: voters thought they were voting on getting rid of the tax, not dissolving the village.

“We had several people that said, ‘I didn’t know what I was voting for, I didn’t understand it.’ It became bad. A lot of people were upset. A lot of people were angry,” Hunt said. “He took away people’s voice.”

Hunt echoed Pringle that the village had a plan to deal with the fiscal emergency.

“I love this town, and I love these people, and I’ve never seen anything like that before in my life,” she said. “I just hope for the best. I just want them [voters] to get another shot at what they feel is right, the right thing to do, and I want them to make their vote based on facts.”

A government that’s ‘not adding value’

Roosa said the lack of fiscal responsibility the village has displayed over the years led to the dissolve issue.

“That’s the big thing that kind of motivated me to get the petition going,” he said. “Originally, I did not even know about all those issues going in, but I quickly discovered them. It seemed like there was no drive to remedy the fiscal situation. So at that point, I decided that I think it’d be best to dissolve the village, and let the township take over.”

Roosa said getting rid of the one percent earnings tax would be a big mistake because then they’d have no revenue to right the fiscal wrongs.

“I heard no talk of that in the council meetings,” he said.

At one point, Roosa said he made a motion in June or July to repeal the one percent income tax.

“Nobody else seconded it, and it just died. I think that’s a lot of talk just to sway people’s opinion,” he said.

Roosa said he was just one person on a council of six, and he was counting on a lot of the “seasoned folks” on council to take some initial initiative. Still, there’s no much space to cut costs, he said.

“I just also see it as a government that isn’t really adding any value,” he said.

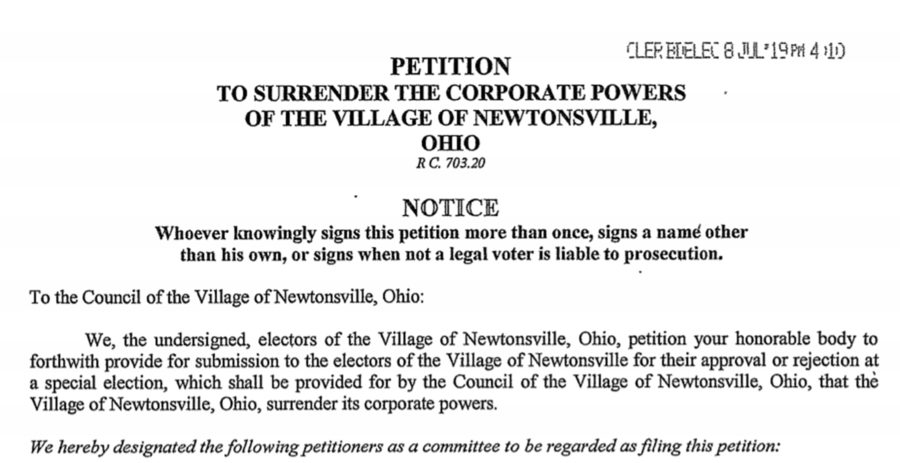

As for accusations that he misled voters or those who signed the petition to get the issue on the ballot at all, Roosa said he thinks he was “pretty clear.” He said the petition stated the matter was to surrender corporate powers.

The petitions, obtained by The Sun, do state in bold capped letters at the top, “Petition to surrender the corporate powers of the village of Newtonsville.”

Roosa said he’s open to help where he can in the transition process, as the village folds into Wayne Township.

“I don’t know what that looks like exactly, but I’m definitely not totally out now that it’s done,” he said.

Roosa said the hope to do another vote is “insane” because in the Nov. 5 election, there weren’t candidates for mayor or council.

“So I mean, just within the village, there’s no interest, either. Nobody shows up at the meetings. It’s pretty much just a quaint form of government that’s no longer necessary, especially for a small village of 400,” he said.

‘Smooth and painless’ transition

Teresa Hinners, trustee in Wayne Township, addressed some of the concerns Newtonsville residents and government officials may have about the transition. For example, she noted that village council passed a resolution to maintain maintenance of the administration building through the transition, which would include electricity and heating.

However, no new event activities can be scheduled in the building unless both the township and the village agree to it.

The township will continue to provide fire and EMS services as it’s already been doing, along with road repair and snow removal.

As for zoning, Hinners would know about this area, as she’s the director of zoning for the township. The plan is to put a moratorium in place since the village didn’t have it’s own zoning. Hinners said there’s a lot of documentation to go through.

She said by the middle of 2020, the township hopes to have the zoning issue figured out.

Another issue, which the township had discussed at its November meeting, was street lights. To maintain those street lights is $5,000 annually. Hinners said that responsibility still falls to the village for now.

On Dec. 4, the township, village officials, county officials, and the State Auditor’s Office are set to meet again. Hinners hopes they do discuss the police department issue, noting that’s a situation in “limbo.”

The township does not have a contracted sheriff’s deputy or its own police department. Hinners said there has been no talk as of yet about the township having its own police department.

“This is a new process; none of us have been through this,” Hinners said.

She cautioned residents that government takes time, but that the township hopes to make it a “smooth process” and “painless as possible.” She also encouraged anyone who has questions and concerns to attend township meetings, and/or call.

Hinners also said the township is planning on adding a button to its website with all the latest information about Newtonsville.

The township’s website is http://www.wayne-township.org/.

Hinners had one more note of reassurance to Newtonsville residents, “They’re still the same people they were a month ago.”

The reporting of Kelly Cantwell, previous editor, contributed to this report.